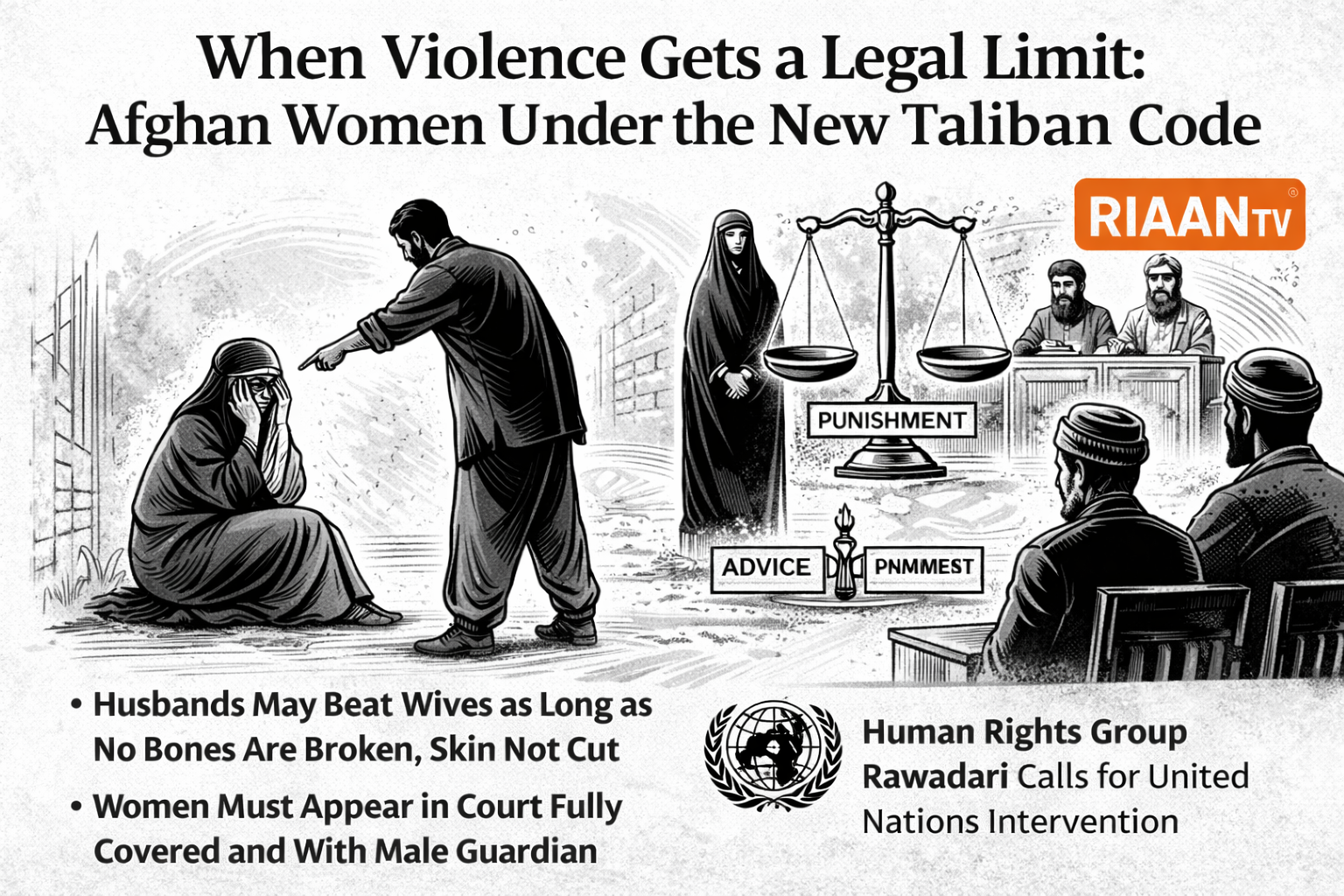

Afghanistan’s new penal code has triggered alarm among women’s rights observers after provisions explicitly allow husbands to physically punish wives and children as long as bones are not broken and skin is not cut. Signed by Taliban leader Hibatullah Akhundzada, the law does not criminalise domestic violence — it regulates its severity, placing a legal boundary around how much harm is considered acceptable inside the home.

The code formalises male authority within the family. Women seeking justice must appear in court fully covered and accompanied by a male guardian, a requirement that effectively places survivors under the supervision of the same social structure they may be trying to report. Even when abuse is proven, punishment remains minimal unless injuries are visibly severe. The legal burden therefore shifts from preventing violence to measuring its physical extent.

Restrictions extend beyond physical safety. Women may face up to three months’ imprisonment for visiting relatives without a husband’s permission, transforming personal movement into a punishable act. Human rights organisation Rawadari has called for United Nations intervention, while UN Special Rapporteur Reem Alsalem warned that systems built around guardianship risk institutionalising control rather than providing protection.

The law also differentiates punishment based on social hierarchy — religious scholars may receive advice, while lower-class offenders face harsher penalties. Critics say this embeds inequality into the justice process itself, combining gender and class vulnerability within one legal framework.

For Afghan women, the implications are broader than individual clauses. A legal system that defines violence by visible injury rather than coercion or fear leaves psychological harm unrecognised and reporting structurally difficult. In practice, protection becomes conditional, and safety depends not on the absence of abuse, but on whether its evidence meets a prescribed threshold.

Rights observers warn that such frameworks move domestic power from social practice into state-endorsed regulation turning private control into enforceable order. In doing so, the law does not simply fail to protect women; it reshapes the meaning of protection itself.